Public Employee Press

Everyday Heroes

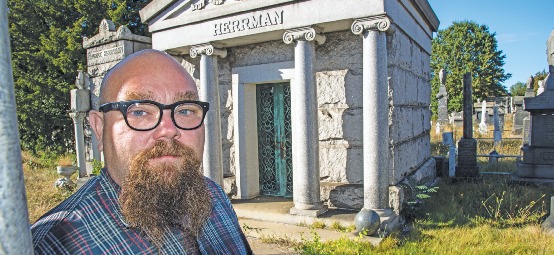

A bridge maintainer’s mitzvah

A Local 1931 member’s good deed of cleaning up Bayside Cemetery honors the dead and revives a part of New York City’s forgotten history

For years Anthony Pisciotta, a Bridge and Tunnel Maintainer in Local 1931, drove past Bayside Cemetery every day. He saw the long neglected Jewish burial ground near Kennedy Airport that was overgrown with knee-high weeds and tangles of brush and trees.

Pisciotta found felled tombstones scrawled with graffiti, mausoleums and coffins busted open and robbed of valuables. The grounds were littered with garbage and desecrated and exposed corpses.

“I was incensed at what had become of this final resting place,” said Pisciotta, who lives in the Bronx. “I could complain or I could improve the situation.”

The synagogue that owns the Bayside graveyard, Shaare Zedek, had stopped hiring groundskeepers years ago. So Pisciotta, though not Jewish, performed a mitzvah, a good deed.

He began a restoration project that quickly became his consuming passion. Pisciotta’s voluntary mission is to restore dignity to the men, women and children buried in Bayside Cemetery. Only three people who are not Jewish are lain there.

Pisciotta spends most Sundays soldering the iron gates of vandalized mausoleums and righting and resetting hundreds of damaged and toppled gravestones, using a special pulley and adhesive and help from his young son.

Pisciotta’s clean-up of the 1861 graveyard chronicles centuries of New York City history. As he clears graves, Pisciotta finds tombs for fallen soldiers from forgotten wars. Pisciotta has found Civil War veterans, an Ostrich-feather merchant who died on the Titanic, two victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, and labor leader Sam Gompers’ son and daughter-in-law.

The U.S. Marines named Anthony Pisciotta an honorary Marine for restoring the headstone of Pfc. Irving Aron, who was killed in Nicaragua in 1930.

“A child Silvia Harris is buried alongside her nanny, Agnes,” Pisciotta said. He then recalled how they and 1,300 German Americans set sail June 14, 1904, on the General Slocum, a Brooklyn steamship charter that carried a church group to Long Island for a picnic only to catch fire and sink. Over 1,020 passengers died.

“There is the cluster of graves of hundreds of children who died of Spanish Influenza; they’re all buried in one section,” Pisciotta said. Though not a scholar, Pisciotta researches the genealogies of individuals buried in Bayside Cemetery, often connecting living relatives to their 19th century ancestors.

“Some want to leave the past buried,” Pisciotta said. “Others, like one family in Connecticut, are extremely grateful. They included me as a guest at their family reunion.”

Pisciotta leads tours through Bayside Cemetery not for the macabre, but for the scraps of history he pieces together to weave a history of one of the largest immigrant communities — Jews who came to America from Germany at the dawn of the Industrial Age and settled in the metropolis of New York City. Not a few of those buried were exhumed from graves in Manhattan and their remains reinterred at Bayside.

Word of Pisciotta’s work spread to other Jewish congregations and the Frederick Douglass Cemetery, an African American burial ground on Staten Island. “We all hope our ancestors would be respected, that their final resting place is respected,” said Pisciotta. “So this is my way of honoring their last wishes and memory.”